From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigationJump to search This article is about raw food consumption in humans. For a raw diet for cats or dogs, see Raw feeding.

Raw vegan Thanksgiving “Turkey”

Raw foodism, also known as rawism or following a raw food diet, is the dietary practice of eating only or mostly food that is uncooked and unprocessed. Depending on the philosophy, or type of lifestyle and results desired, raw food diets may include a selection of fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, eggs, fish, meat, and dairy products.[1] The diet may also include simply processed foods, such as various types of sprouted seeds, cheese, and fermented foods such as yogurts, kefir, kombucha, or sauerkraut, but generally not foods that have been pasteurized, homogenized, or produced with the use of synthetic pesticides, fertilizers, solvents, and food additives.

Medical authorities have described raw foodism as a fad diet.[2][3] Raw food diets, specifically raw veganism, fail to provide essential minerals and nutrients such as calcium, iron and protein.[2][4][5] Claims held by raw food proponents are pseudoscientific.[6]:44

Contents

- 1 Varieties

- 2 History

- 3 Claims

- 4 Health effects

- 5 Role of cooking in human evolution

- 6 See also

- 7 References

Varieties

Raw food diets are diets composed entirely or mostly of food that is uncooked or that is cooked at low temperatures.[7]

Raw veganism

Raw vegan apple pie Main article: Raw veganism

A raw vegan diet consists of unprocessed, raw plant foods that have not been heated above 40–49 °C (104–120 °F). Typical foods included in raw food diets are fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, and sprouted grains and legumes.

Among raw vegans are subgroups, such as fruitarians, juicearians, or sproutarians. Fruitarians eat primarily or exclusively fruits, berries, seeds, and nuts. Juicearians process their raw plant foods into juice. Sproutarians adhere to a diet consisting mainly of sprouted seeds.

Raw animal food diets

Main article: Raw animal food diets

| Steak tartare with raw egg, capers and onions | |

| Main ingredients | Raw beef |

|---|---|

| Variations | Tartare aller-retour |

| Cookbook: Steak tartare Media: Steak tartare |

Included in raw animal food diets are any food that can be eaten raw, such as uncooked, unprocessed raw muscle-meats/organ-meats/eggs, raw dairy, and aged, raw animal foods such as century eggs, fermented meat/fish/shellfish/kefir, as well as vegetables/fruits/nuts/sprouts/honey, but in general not raw grains, raw beans, and raw soy. Raw foods included on such diets have not been heated above 40 °C (104 °F).[8]

Examples of raw animal food diets include the Primal Diet,[9][10] anopsology (otherwise known as “Instinctive Eating” or “Instincto”), and the Raw Paleolithic diet[11][12] (otherwise known as the “Raw Meat Diet”).[13]

The Primal Diet consists of fatty meats, organ meats, dairy, honey, minimal fruit and vegetable juices, and coconut products, all raw, whereas the “Raw, Paleolithic Diet”,[12][14] is a raw version of the (cooked) Paleolithic Diet, incorporating large amounts of raw animal foods such as meats/organ-meats, seafood, eggs, and some raw plant-foods, but usually avoiding non-Paleo foods such as raw dairy, grains, and legumes.[12][13]

A number of traditional aboriginal diets consisted of large quantities of raw meats, organ meats, and berries, including the traditional diet of the Nenets tribe of Siberia and the Inuit people.[15][16][17]

History

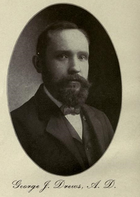

Eugene Christian and George J. Drews, founders of the American raw food movement

Perhaps the first documented evidence (in the hagiography of Yafqərännä Ǝgziˀ) of a commitment to raw food was by the Ethiopian monk Qozmos, who in the late 1300s CE committed to the ascetic discipline of eating only uncooked food.[18][19] This posed a problem for his Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church monastery because he refused to eat the bread of the Eucharist, which is cooked. As a result, he fled the church and went to live with the Jewish community of the Beta Israel.[18][19]

Contemporary raw food diets were first developed in Switzerland by Maximilian Bircher-Benner (1867 – 1939), who was influenced as a young man by the German Lebensreform movement, which saw civilization as corrupt and sought to go “back to nature”; it embraced holistic medicine, nudism, free love, exercise and other outdoors activity, and foods that it judged were more “natural”.[6]:41–43 Bircher-Benner eventually adopted a vegetarian diet, but took that further and decided that raw food was what humans were really meant to eat; he was influenced by Charles Darwin‘s ideas that humans were just another kind of animal and Bircher-Benner noted that other animals do not cook their food.[6]:41–43 In 1904 he opened a sanatorium in the mountains outside of Zurich called “Lebendinge Kraft” or “Vital Force,” a technical term in the Lebensreform movement that referred especially to sunlight; he and others believed that this energy was more “concentrated” in plants than in meat, and was diminished by cooking.[6]:41–43 Patients in the clinic were fed raw foods, including muesli, which was created there.[6]:41–43 These ideas were influential to Ann Wigmore a notable raw food advocate but were dismissed by scientists and the medical profession as quackery.[6]:41–43

One of the earliest books to advocate raw foodism was Eugene Christian‘s Uncooked Foods and How to Use Them, 1904.[20] Other proponents from the early part of the twentieth century include Californian fruit grower Otto Carque (author of The Foundation of All Reform, 1904), George Julius Drews (author of Unfired Food and Trophotherapy, 1912), Bernarr Macfadden and Herbert Shelton. Drews influenced John and Vera Richter to open America’s first raw food restaurant “The Eutropheon” in 1917.[20]

Shelton was arrested, jailed, and fined numerous times for practicing medicine without a license during his career as an advocate of rawism and other alternative health and diet philosophies.[21] Shelton’s legacy, as popularized by books like Fit for Life by Harvey and Marilyn Diamond, has been deemed “pseudonutrition” by the National Council Against Health Fraud.[22]

In the 1970s, Norman W. Walker (inventor of the Norwalk Juicing Press) popularized raw food dieting.[23] Leslie Kenton‘s book Raw Energy – Eat Your Way to Radiant Health, published in 1984, added popularity to foods such as sprouts, seeds, and fresh vegetable juices.[24] The book advocates a diet of 75% raw food, which it claims will prevent degenerative diseases, slow the effects of aging, provide enhanced energy, and boost emotional balance; it cites examples such as the sprouted-seed-enriched diets of the long-lived Hunza people and Gerson therapy, an unhealthy, dangerous and potentially very harmful[25][26] raw juice-based diet and detoxification regime claimed to treat cancer.[25]

Claims

Claims held by raw food proponents include:

- That heating food above 104–118 °F (40–48 °C) starts to degrade and destroy the enzymes in raw food that aid digestion. Enzymes in food play no significant role in the digestive process, prior to being digested themselves.[6]:44

- That raw foods have higher nutrient values than foods that have been cooked.[6]:44 In reality, whether cooking degrades nutrients or increases their availability, or both, depends on the food and how it is cooked.[6]:44[27]

- That cooked foods, and especially meat, contain harmful toxins, which can cause chronic disease and other problems, including trans fatty acids produced by heating oil, acrylamide produced by frying, advanced glycation end products (AGEs), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.[6]:44–45 While it is true that a healthy diet minimizes fried food and red meat, not all cooked food contains harmful chemicals (a serving of french fries has 200 times the AGEs of a bowl of cooked oatmeal), and a diet containing a normal mix of cooked and raw food does not shorten life.[6]:44–45[28][29] According to the American Cancer Society, it is not clear, as of 2013, whether acrylamide consumption affects people’s risk of getting cancer.[30]

Health effects

A close-up of a raw food dish

A raw food diet is likely to impair the development of children and infants.[31] Care is required in planning a raw vegan diet, especially for children,[32] as there may not be enough vitamin B12, vitamin D, and calories for a growing child on a totally raw vegan diet. Fuhrman fed his own four children raw and cooked vegetables, fruits, nuts, grains, beans, and occasionally eggs.[33]

Food poisoning is a health risk for all people eating raw foods, and increased demand for raw foods is associated with greater incidence of foodborne illness,[34] especially for raw meat, fish, and shellfish.[35][36] Outbreaks of gastroenteritis among consumers of raw and undercooked animal products (including smoked, pickled or dried animal products[35]) are well-documented, and include raw meat,[35][37][38] raw organ meat,[37] raw fish (whether ocean-going or freshwater),[35][36][38] shellfish,[39] raw milk and products made from raw milk,[40][41][42] and raw eggs.[43]

Studies have associated raw food dieting with loss of body weight and low bone mass.[44][45][46]

One review stated that “Many raw foods are toxic and only become safe after they have been cooked. Some raw foods contain substances that destroy vitamins, interfere with digestive enzymes or damage the walls of the intestine. Raw meat can be contaminated with bacteria which would be destroyed by cooking; raw fish can contain substances that interfere with vitamin B1 (anti-thiaminases)”[47]

Role of cooking in human evolution

Richard Wrangham, professor of biological anthropology at Harvard University,[48] proposes that cooked food played a pivotal role in human evolution. Evidence of a cooked diet, according to Wrangham, can be seen as far back as 1.8 million years ago in the anatomical adaptations of Homo erectus. Reduction in the size of teeth and jaw in H. erectus indicate a softer diet, requiring less chewing time. This combined with a smaller gut and larger brain indicate to Wrangham that H. erectus was eating a higher quality diet than its predecessors.[49] To explain a decreased gut providing the amount of energy required for an increased brain size, Wrangham links his research on the digestive effects of cooked versus raw foods with the lower reproductive abilities of female raw foodists, and BMI in both sexes, to support his hypothesis that cooked starches provided the energy necessary to fuel evolution from H. erectus to H. sapiens.[50]

Theories opposed to Wrangham’s include that of Leslie Aiello, professor of biological anthropology at University College London, and physiologist Peter Wheeler. Aiello and Wheeler believe it was soft animal foods, including bone marrow and brains, which contributed to humans developing the characteristics Wrangham attributes to cooked foods.[51] Further, archaeological evidence suggests that cooking fires began in earnest only around 250 kya, when ancient hearths, earth ovens, burnt animal bones, and flint appear regularly across Europe and the Middle East. Two million years ago, the only sign of fire is burnt earth with human remains, which many anthropologists consider coincidence rather than evidence of intentional fire.[52] Many anthropologists believe the increases in human brain-size occurred well before the advent of cooking, due to a shift away from the consumption of nuts and berries to the consumption of raw meat.[51][53][54]

See also

- Amílcar de Sousa

- Béla Bicsérdy

- Bernando LaPallo

- Cooking

- Fruitarianism

- Green smoothie

- List of diets

- Orthopathy

- Raw food diet for pets

- Category:Raw foodists

- Rejuvelac

- Sattvic diet

- Taboo food and drink

- Xerophagy, a form of fasting

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Raw foodism. |

References

Wong, Cathy (17 September 2007). “Raw Food Diet”. About.com. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2009. “Are Fad Diets Just a Fad?”. Pharmacy Times. Retrieved August 22, 2019. “Fad diets”. British Dietetic Association. Retrieved August 22, 2019. “Dangers of a Raw Food Diet”. Livestrong. Retrieved August 22, 2019. “Reality Check: 5 Risks of a Raw Vegan Diet”. Scientific American. Retrieved August 22, 2019. Fitzgerald M (2014). Diet Cults: The Surprising Fallacy at the Core of Nutrition Fads and a Guide to Healthy Eating for the Rest of US. Pegasus Books. ISBN978-1-60598-560-2. Kaufman CF (2013). Smith AF, Kraig B (eds.). Cooking Techniques. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America. volume 1 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 537–544. ISBN978-0-19-973496-2. “Primal Dieting: Eat Your Raw food With A Roar!”. Foodenquirer.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-23. Retrieved 2012-01-31. Green, Emily (2001-01-31). “Meat but No Heat – Los Angeles Times”. Articles.latimes.com. Archived from the original on 2011-08-27. Retrieved 2010-05-12. “Vue Weekly: Edmonton’s 100% Independent Weekly: Well met, raw meat: hoorah for raw!”. Vueweekly.com. Retrieved 2015-04-10. “Raw Paleo Diet – The Raw Paleolithic Diet & Lifestyle!”. Rawpaleodiet.com. Archived from the original on 2008-10-30. Retrieved 2008-11-07. “Raw Paleo Diet – RVAF Systems Overview”. Archived from the original on 2012-07-17. More for less (2005-06-12). “The raw meat diet: do you have the stomach for the latest celebrity food fad? – Health News, Health & Wellbeing – The Independent”. London: Independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2008-11-07. “Raw Paleo Diet – The Raw Paleolithic Diet & Lifestyle!”. Rawpaleodiet.com. Archived from the original on 2008-10-30. Retrieved 2008-11-07. Viestad, Andreas (2008-05-14). “Where Home Cooking Gets the Cold Shoulder”. Washingtonpost.com. Archived from the original on 2012-11-06. Retrieved 2008-11-07. “BBC NEWS | In pictures: Cooking in the Danger Zone, Rotten walrus meat”. News.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2009-01-12. Retrieved 2008-11-07. [1]Archived December 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Binns, John (2016-11-28). The Orthodox Church of Ethiopia: A History. I.B.Tauris. p. 30. ISBN9781786720375. Kaplan, Steven. “Qozmos.” Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: O-X: Vol. 4, edited by Siegbert Uhlig, Harrassowitz, 2010, p. 303. Berry, Rynn. (2007). “Raw Foodism”. In Andrew F. Smith. The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. Oxford University Press. pp. 493-494. ISBN978-0-19-530796-2Herbert M. Shelton Jarvis, Ph.D., William T. “Fasting”. National Council Against Health Fraud. Retrieved 8 April 2014. Coull, Lauren. (2015). “Raw Food”. In Andrew F. Smith. Savoring Gotham: A Food Lover’s Companion to New York City. Oxford University Press. pp. 490-491. ISBN978-0-19-045465-4“Raw energy”. New Insight. Archived from the original on October 25, 2003. Retrieved 2008-11-07. “Gerson Therapy”. American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on April 20, 2009. Retrieved April 22, 2009. UK, Cancer Research (1 December 2015). “Gerson therapy”. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Palermo, M; Pellegrini, N; Fogliano, V (April 2014). “Review: The effect of cooking on the phytochemical content of vegetables”. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 94 (6): 1057–70. doi:10.1002/jsfa.6478. PMID24227349. “Chemicals in Meat Cooked at High Temperatures and Cancer Risk – National Cancer Institute”. Cancer.gov. 2018-04-02. Archived from the original on 2010-12-21. Retrieved 2012-01-31. Scientific Committee on Food – Task Force on PAH (4 December 2002). “PAH – Occurrence in foods, dietary exposure and health effects” (PDF). European Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 2014-05-12. “Acrylamide”. American Cancer Society. 1 October 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2014. Cunningham, E (2004). “What is a raw foods diet and are there any risks or benefits associated with it?”. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 104 (10): 1623. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2004.08.016. PMID15389429. Messina, V; Mangels, AR (2001). “Considerations in planning vegan diets: children”. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 101 (6): 661–9. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00167-5. PMID11424545. Rachel Breitman. “The raw food diet: a half-baked idea for kids? — JSCMS”. Jscms.jrn.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on May 10, 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-07. Lee, CC; Lam, MS (1996). “Foodborne diseases”. Singapore Medical Journal. 37 (2): 197–204. PMID8942264. Macpherson, CN (2005). “Human behaviour and the epidemiology of parasitic zoonoses”. International Journal for Parasitology. 35 (11–12): 1319–31. doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.06.004. PMID16102769. Lun, ZR; Gasser, RB; Lai, DH; Li, AX; Zhu, XQ; Yu, XB; Fang, YY (2005). “Clonorchiasis: a key foodborne zoonosis in China”. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 5 (1): 31–41. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01252-6. PMID15620559. Yoshida, H; Matsuo, M; Miyoshi, T; Uchino, K; Nakaguchi, H; Fukumoto, T; Teranaka, Y; Tanaka, T (2007). “An outbreak of cryptosporidiosis suspected to be related to contaminated food, October 2006, Sakai City, Japan”. Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases. 60 (6): 405–7. PMID18032847. Archived from the original on 2012-02-14. Retrieved 2014-02-08. Pozio, E (2003). “Foodborne and waterborne parasites”. Acta Microbiologica Polonica. 52 Suppl: 83–96. PMID15058817. Su, YC; Liu, C (2007). “Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a concern of seafood safety”. Food Microbiology. 24 (6): 549–58. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2007.01.005. PMID17418305. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2008). “Escherichia coli 0157:H7 infections in children associated with raw milk and raw colostrum from cows—California, 2006”. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 57 (23): 625–8. PMID18551097. Archived from the original on 2017-06-15. Donnelly, Catherine W. (1990). “Concerns of Microbial Pathogens in Association with Dairy Foods”. Journal of Dairy Science. 73 (6): 1656–61. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(90)78838-8. PMID2200814. Doyle, MP (1991). “Escherichia coli O157:H7 and its significance in foods”. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 12 (4): 289–301. doi:10.1016/0168-1605(91)90143-D. PMID1854598. Cox, JM (1995). “Salmonella enteritidis: the egg and I”. Australian Veterinary Journal. 72 (3): 108–15. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.1995.tb15022.x. PMID7611983. Douglass JM, Rasgon IM, Fleiss PM. (1985). Effects of a raw food diet on hypertension and obesity. South Med J 78: 841–844. C. Koebnick, C. Strassner, I. Hoffmann, C. Leitzmann. (1999). Consequences of a long-term raw food diet on body weight and menstruation: results of a questionnaire surveyArchived 2017-10-15 at the Wayback Machine. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 43 (2): 69–79. Fontana L, Shew JL, Holloszy JO, Villareal DT. (2005). Low bone mass in subjects on a long-term raw vegetarian dietArchived 2018-04-09 at the Wayback Machine. Arch Intern Med 165 (6): 684-689. Bender, Arnold E. (1986). Health or Hoax?: The Truth About Health Foods and Diets. Sphere Books. p. 40. ISBN0-7221-1557-1“Richard W. Wrangham”. heb.fas.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2016-09-29. Gorman, Rachael Moeller. “Evolving Bigger Brains through Cooking: A Q&A with Richard Wrangham”. Archived from the original on 2016-10-04. Retrieved 2016-09-29. Carmody, Rachel N.; Wrangham, Richard W. (2009-10-01). “The energetic significance of cooking”. Journal of Human Evolution. Paleoanthropology Meets Primatology. 57 (4): 379–391. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.02.011. PMID19732938. Pennisi, Elizabeth (1999-03-26). “Did Cooked Tubers Spur the Evolution of Big Brains?”. Science. 283 (5410): 2004–2005. doi:10.1126/science.283.5410.2004. PMID10206901. Archived from the original on 2011-03-10 – via CogWeb.UCLA.edu. Gorman, RM (2008). “Cooking up bigger brains”. Scientific American. 298 (1): 102, 104–5. Bibcode:2008SciAm.298a.102G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0108-102. PMID18225702. McBroom, Patricia (1999-06-14). “Meat-eating was essential for human evolution, says UC Berkeley anthropologist specializing in diet” (Press release). University of California at Berkeley Public Information Office. Archived from the original on 2012-01-30. Retrieved 2012-01-31. Mann, Neil (2007-09-01). “Meat in the human diet: an anthropological perspective”. Nutrition & Dietetics. 64 (s4): S102–S107. doi:10.1111/j.1747-0080.2007.00194.x. Archived from the original on 2012-09-11. Retrieved 2012-01-31.